The Facebook and Instagram “Ten-Year Challenge” has resurfaced once again, inviting users to share two personal photos taken roughly a decade apart. While the trend is commonly perceived as a nostalgic or playful way to reflect on personal change, it continues to raise broader questions about privacy, data reuse, and how seemingly simple online behaviors can contribute to long-term data ecosystems.

What makes this discussion relevant in 2026 is not the trend itself, but the technological and regulatory environment in which it exists. Social media platforms, data analytics, and machine learning systems have matured significantly, making historical personal data more valuable than ever.

As these concerns gained traction, it became important to revisit how the challenge originated and why it still matters years later.

How the Ten-Year Challenge Became a Global Phenomenon

The Ten-Year Challenge first gained widespread attention in early 2019, spreading rapidly across Facebook, Instagram, and later other platforms. Users were encouraged to post a “then” photo from around 2009 alongside a “now” photo from 2019. Celebrities, brands, and public figures amplified the trend, accelerating its global reach.

The appeal was simple:

- It relied on existing personal content

- It encouraged self-expression rather than technical participation

- It created a shared cultural moment across age groups

Over time, similar challenges emerged, reinforcing a pattern where viral participation unintentionally produces large volumes of structured personal data.

As participation grew, privacy specialists began examining why such content could be sensitive beyond its social value.

Why Structured Personal Data Draws Attention

Modern digital systems do not treat photos merely as images. When combined with contextual signals, they become structured and classified data points. A single image can include or imply:

- Time and date information

- Identity and biometric features

- Social connections and engagement patterns

- Behavioral signals such as posting habits

When images are intentionally paired across time, as in the Ten-Year Challenge, they form a basic time-series dataset. This naturally leads to questions about how such data could be analyzed or repurposed.

To understand why this matters, it helps to look at how machine learning systems work.

Machine Learning and the Value of Longitudinal Data

Machine learning systems rely on repeated exposure to patterns. Longitudinal data — data collected over time — is especially valuable because it allows systems to:

- Detect change and stability

- Identify aging or progression trends

- Improve prediction accuracy

- Reduce uncertainty in classification models

Examples of how such data can be useful include:

- Facial recognition robustness testing

- Age estimation research

- Identity verification improvements

- Behavioral analytics

SEE ALSO: Can you predict who will win the US election?

Importantly, none of this implies confirmed misuse. However, it illustrates why privacy experts pay close attention to trends that encourage standardized, time-linked data sharing.

At this point, it becomes useful to step back and examine how raw data evolves into insight.

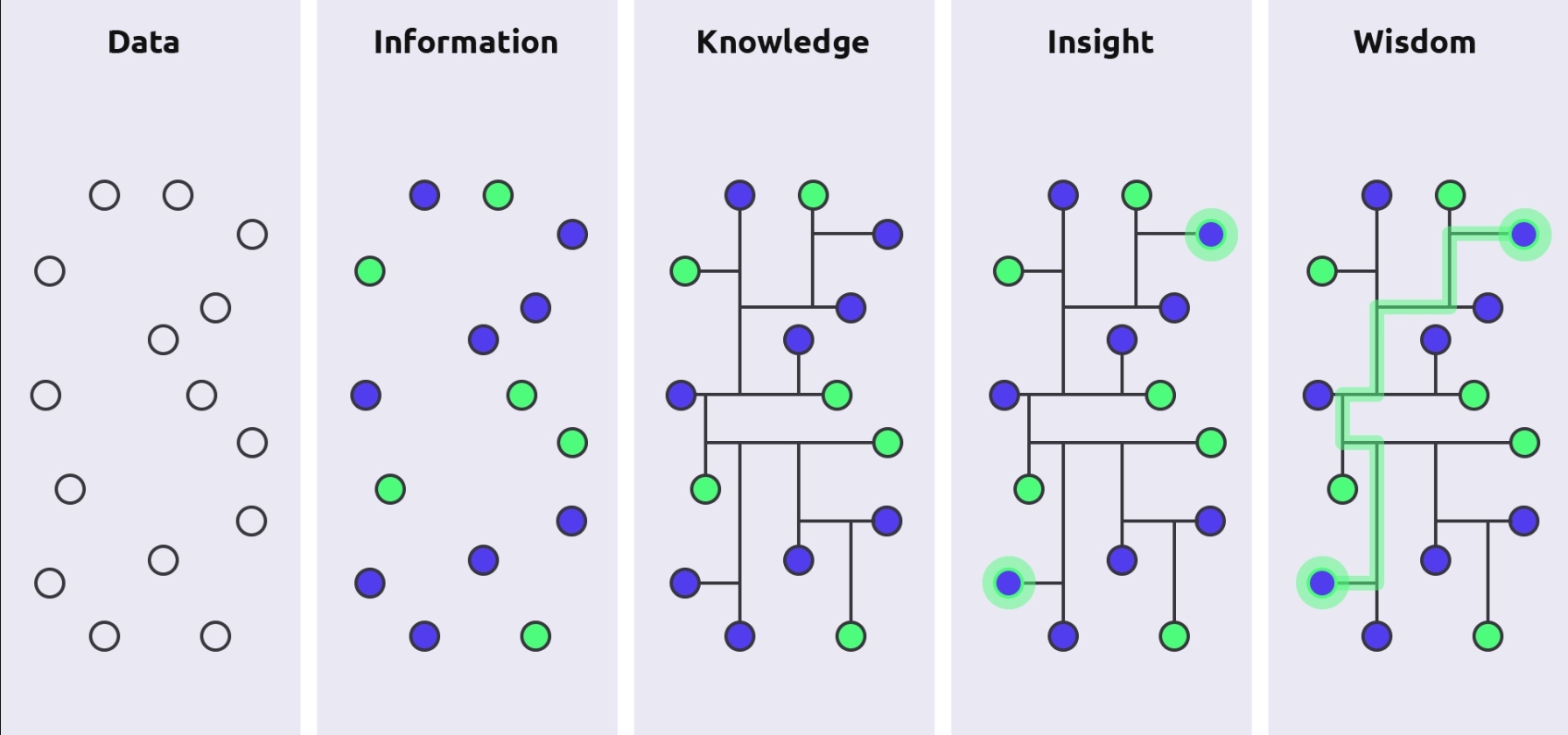

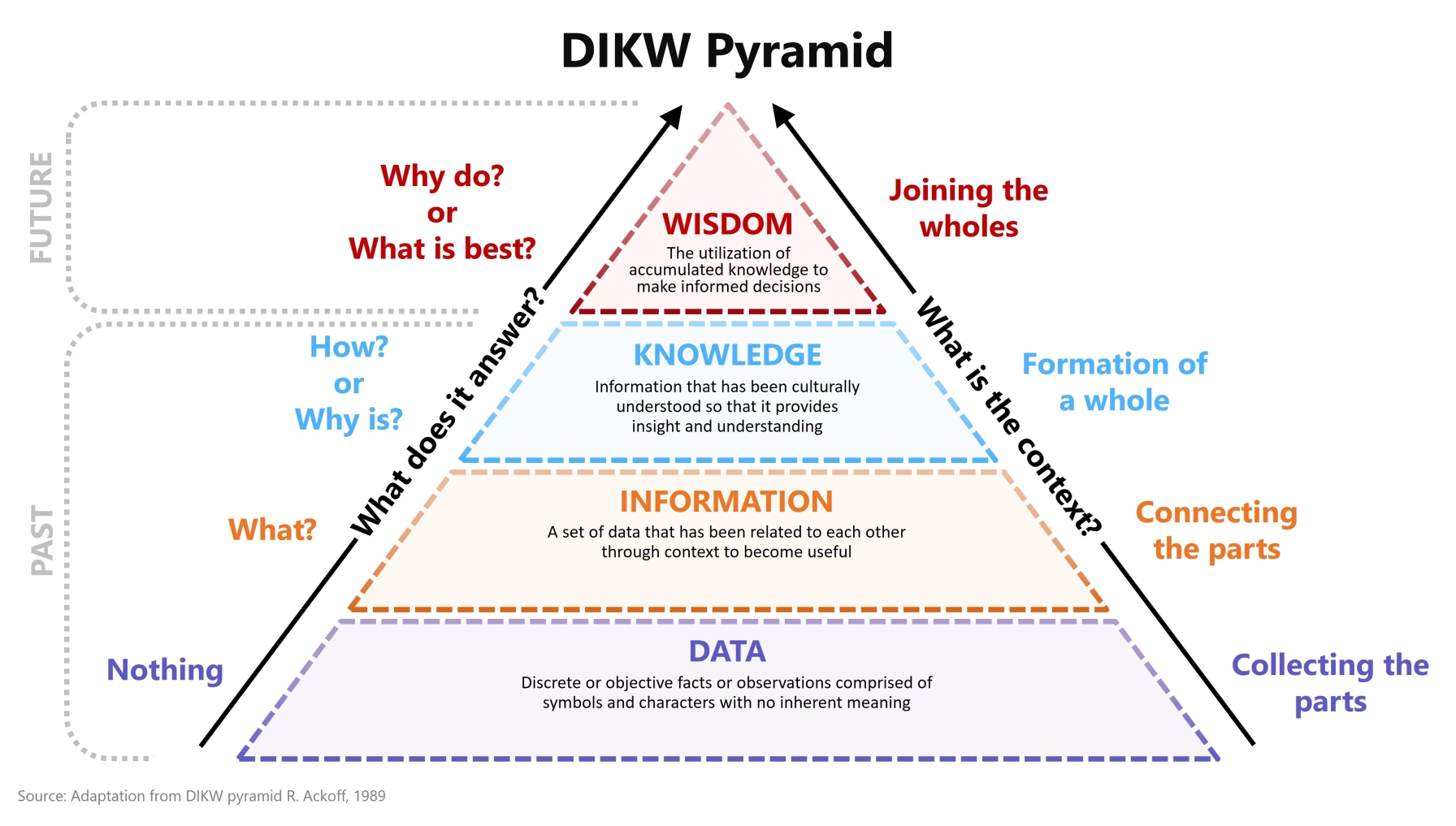

The DIKW Pyramid as a Visual Mental Model

The Data–Information–Knowledge–Wisdom (DIKW) pyramid is a widely used conceptual model for understanding data transformation.

At its base is Data:

- Individual photos uploaded by users

Above that is Information:

- Photos linked to timestamps, identities, and social context

Next is Knowledge:

- Patterns extracted from large collections of similar data

At the top is Wisdom:

- Automated or human decisions based on those patterns

As data moves upward through this pyramid, its value increases — but so does the potential impact on privacy. Users typically engage at the data level, while platforms and analytics systems operate closer to the top.

This distinction explains why personal data can feel harmless at the point of sharing yet become sensitive later.

Personal Data Inference and Third Parties

Social platforms act as primary data controllers, but they are not the only actors involved. Personal data can also be:

- Processed by advertising and analytics partners

- Accessed by third-party applications

- Used in academic or commercial research

- Scraped or misused by malicious actors

One of the most significant risks comes from inferred data — information that is derived rather than explicitly provided. Inference can reveal:

- Age ranges

- Behavioral traits

- Social influence

- Risk profiles

This inferred layer often exists outside the user's direct awareness.

To clarify common misunderstandings, a brief reality check is useful.

Machine Learning: Myths vs Reality

Myth: “Old photos are no longer useful.”

Reality: Historical data enables trend and progression analysis, making it especially valuable.

Myth: “Public data is free of privacy risk.”

Reality: Aggregation and inference can create new risks even from public content.

Myth: “If a platform denies using data, the concern disappears.”

Reality: Broader ecosystems include partners, tools, and secondary uses beyond the original platform.

With these realities in mind, it is natural to ask what this means for the future.

What This Means Over the Next 5–10 Years

Looking ahead, several developments are likely:

- Increased reliance on inferred and historical data

- More advanced biometric and behavioral analytics

- Stronger regulatory oversight and enforcement

- Growing complexity in managing personal digital footprints

At the same time, user awareness is expected to increase, though navigating privacy settings and consent mechanisms may become more challenging.

Recommended Actions

- Review privacy and tagging settings regularly

- Limit participation in trends that can potentially standardize personal data over time

- Be cautious about long-term visibility of personal images by platforms or services

- Understand the difference between shared and inferred data

Conclusion

The Facebook or Instagram Ten-Year Challenge highlights how digital culture, machine learning, and privacy intersect in subtle but meaningful ways. While there is no confirmed evidence that such images are used for machine learning training, the broader lesson remains unchanged: personal data rarely stays confined to its original context. Understanding how data evolves — from raw input to inference and decision-making — empowers users to participate more thoughtfully in the digital environments they rely on every day.